Kodo Sawaki (1880-1965) was an influential Japanese Zen master, known for revitalizing the practice of Sōtō Zen in Japan in the 20th century. He was born in Tsu, Japan, and orphaned at an early age. Despite a difficult childhood following the death of his mother, Sawaki became interested in Zen Buddhism with the vocation of becoming a monk.

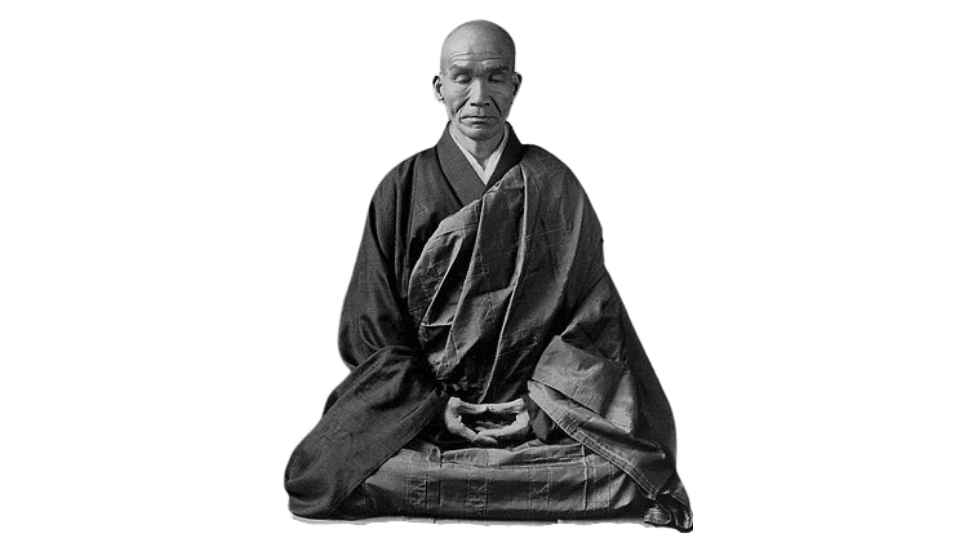

The Monk Kodo Sawaki

In 1896, he set out for Eihei-ji, but once there he faced numerous difficulties. Without a formal recommendation, he was unable to immediately become a Zen monk, so he had to take up the role of a servant.

Despite this, he managed to learn the practice of zazen. Finally, in 1897, under the guidance of Sawada Koho Oshō at the Kyūshū temple, he was ordained as a Zen monk with the name Kōdō. He stayed with this teacher for two years. Later, he met Fueoka Sunum Oshō, who taught him the true path: not to seek satori or any other goal, but simply to sit in zazen.

Always Dedicated to the Practice of Zazen

In 1908, at the age of 29, Master Kodo Sawaki entered the Horyu-ji school in Nara, where he studied philosophy without abandoning his consistent practice of zazen or his study of Dogen. In 1912, he was appointed the first assistant at the Yōsen-ji dojo. Later, he lived in solitude for a period, intensely dedicated to the practice of Zen meditation in a small temple in the Nara province.

In 1916, he left this retreat to become a professor at the Daiji-ji Sōdō. From 1923, he began traveling across Japan, giving lectures and leading sesshin (meditation retreats). In 1935, he joined Komazawa University as a professor, where he taught Zen literature and led zazen practice. He later took on the role of godo at the Sōji-ji temple. Before the war, in 1940, he was also in charge of the mountain temple, Tengyō Zen-en.

Homeless Kōdō

Throughout his life, Master Kodo Sawaki emphasized the importance of zazen (seated meditation) as the essence of Zen, promoting its practice among both monks and laypeople. He was nicknamed “Homeless Kōdō” because he refused to stay in one temple, instead traveling across Japan teaching and organizing meditation retreats or sesshin.

During the Russo-Japanese War, Sawaki was enlisted in the army, marking a difficult period in his life, although he remained committed to zazen practice. After the war, he returned to Japan and continued teaching in various temples, as well as serving as a professor at Komazawa University.

Master Kodo Sawaki at Antaiji

Kodo Sawaki played a decisive role in transforming Antaiji Temple. Originally founded in 1921 as an academic center for the study of Dogen’s Shōbōgenzō, Antaiji had declined after World War II. In 1949, Master Kodo Sawaki and his disciple Kosho Uchiyama revitalized the temple, turning it into a place dedicated to the pure practice of zazen.

Sawaki’s vision for Antaiji was to move away from the academic and scholarly studies of Buddhism, promoting instead a Zen practice centered on Zen meditation and self-sufficiency. This led to a rigorous lifestyle focused on zazen and formal begging, distancing itself from the larger temples with more institutional approaches. Under Sawaki’s influence, Antaiji became a key center for austere and authentic zazen practice.

His legacy at Antaiji endures, and the emphasis on pure practice that he championed continues to be the foundation of the temple, attracting practitioners from around the world who seek a simple and direct form of Zen.

Master Kodo Sawaki Legacy of the Kesa to Taisen Deshimaru

Kodo Sawaki had a profound influence on Taisen Deshimaru, who became his disciple in 1936 and followed him for nearly 30 years in a close master-disciple relationship. Kodo Sawaki instilled in Deshimaru the importance of zazen as the heart of Zen. Sawaki rejected the institutionalized approach to Buddhism, promoting a simpler and more accessible Zen practice, something Deshimaru adopted and later brought to Europe.

Before his death in 1965, Sawaki passed on his teachings to Deshimaru, entrusting him with his kesa (the traditional monk’s robe) and charging him with the mission of spreading Zen in the West. Deshimaru fulfilled this mandate by traveling to France in 1967, where he established numerous Zen practice centers and popularized the Sōtō school in Europe. Through Sawaki’s influence, Deshimaru continued to promote a Zen practice based on the simplicity and universality of zazen, extending this vision to new cultural contexts.